ST. IVES CROSS.

of the Early Christian Antiquities within the District of Saint Ives.

Chapels.

Soon after the death of Saint Ia, other Christian oratories were built in and near Saint Ives, besides that which owed its foundation immediately to her:

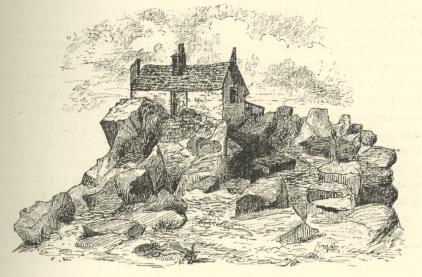

I. The Chapel of Saint Nicholas on the top of the Island. This is still standing, but has for centuries been subjected to such patching and alterations as have perhaps left but little of the original structure. Its latest metamorphosis was when it was transformed into a look-out for the revenue officers. This was probably done some time in the last century; and brick additions were then made to the ancient building, turning it into a sort of cottage, with a low wall on the rock behind, on which the pilots rest their telescopes when scanning the horizon for vessels. The Chapel of Saint Nicholas is mentioned in the ‘Liber Regis,’ says Lysons. Tonkin says:

‘On the island (or peninsula) work of Saint Ives standeth the ruins of an old chapel, wherin God was duly worshipped by our ancestors the Britons, before the Church of St. Ives was erected or endowed.’

Hals says:

‘This town, as Mr. Camden saith, was formerly called Pendenis or Pendunes, the head fort, fortress, or fortified place; probably from the little island here, containing about six acres of ground, on which there stands the ruins of a little old fortification and a chapel.’

Leland also refers to this chapel, as mentioned in our last chapter. Throughout the Borough and Churchwardens’ Account Books, largely transcribed into these pages, are frequent entries of payments made for the repair of this chapel, and the next one to be mentioned.

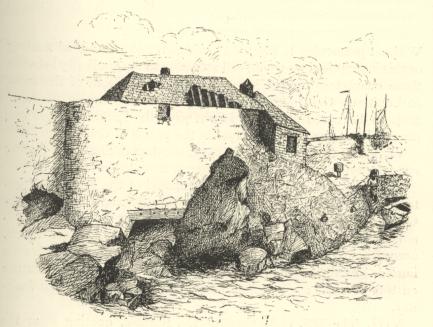

II. The oratory of Saint Leonard, at the spot where the stone pier juts out from the shore. This ancient building is still called ‘The Chaple,’ and the people regard it with some lingering reverence. The Chaple still preserves its original outline, with its eastern end narrowing inwards, and the little narrow doorway in the north wall, having a rude flight of steps leading up to it. Against the inside of the eastern wall are slight remains of the stones which formed the base of the altar. During the Middle Ages the Chaple was especially devoted to the use of the fishermen, who maintained a chaplain to say Mass for them there, they paying him by an offering of fish proportioned to each catch. This office seems to have been continued even after the Reformation, for Warner tells us of a chaplain who, in his time, said prayers there for the fishermen, whenever he was sufficiently sober to do so. For the past hundred years or more, the Chaple has been used as a shelter for the long-shore men of various kinds, for whose benefit a rude seat has been provided, formed of the mast of a ship, and ranged along the wall inside. The Chaple was repaired out of the pier fund; but this having been long discontinued, the venerable oratory was beginning to fall into ruins in 1886, when it was saved and restored by the timely and intelligent action of the Mayor, Mr. Edward Hain, junior.

III. The chapel or oratory which formerly stood on the rocks under Penmester Hill, and which gives its name to the cove and neighbourhood of Porthminster (‘the sandy cove of the church’). In some parts of Cornwall, as at Boscastle, old people still call the church ‘the minster.’ Some years ago the sand was washed down from the top of the beach, close to the Tregenna stream, leaving uncovered a portion of the foundations of this oratory, near which were found two stone coffins with leaden chalices, marking the interment of priests. It was said that these remains were deposited in the museum of Penzance, but I have never seen them. The find was made about the year 1870, and was reported by the local press. The chapel, together with the village of Port minster, was destroyed by French men-of-war, who burned them to the ground in the reign of Henry VI.

IV. At Brunian or Brunnion in Lelant was another ancient chapel, dedicated to Saint Mary. Its site is marked by an old cross, and a carved stone arch which formed the entrance. Close by is a garden which is said to have been originally the burial-ground. The Exeter Episcopal Register records that Thomas Mohun and Isabella his wife, Michael Trenuyd (Trenwith) and Margery Eyr, applied to the Bishop for licence to have Mass celebrated for a year from June 17, 1398, in the Chapel of the Blessed Virgin Mary at ‘Breynyon in parochia Sancti Eunii in Cornubia’ but in the margin are the words ‘Non habuit effectum.’ In the same manuscript, under the date 1410 or thereabouts, it is called the Chapel of Saint Mary Magdalen.

CHAPEL OF ST. NICHOLAS, ST. IVES.

‘THE CHAPLE,’ ST. IVES, FROM THE N.W.

V. At the farm of Trevarrack, in the parish of Towednack, is a croft known as the Chapel Field, where formerly stood the ruins of an ancient oratory. The site was ploughed up in the year 1840, and the remains of the chapel carted away. A few of the carved stones, including a fragment of the ashlar ogee of a window, are to be seen in the garden of the farmhouse, and into the front of the house and inscribed stone from the chapel has been built, concerning which a few words must be said. It is an oblong block of freestone, about three feet by one foot, and the inscription is in early mediæval Latin characters, lightly incised. The stone is high up in the wall, and, being upside down is difficult to make out on a cursory inspection; but the following marks may be distinguished:

Without presuming to hazard a conjecture as to the actual reading of this inscription, we will call attention to the similarity between these characters and the letters marked on the front of the cross at Lanherne Convent, as figured in Blight’s ‘Cornish Crosses.’ It is to be noted also that Blight says the Lanherne cross was removed from an ancient chapel in the parish of Gwinear.

VI. At Higher Tregenna, in 1814, the foundations of a similar old oratory were, according to Lysons, still visible.

VII. The foundations of another chapel of the same kind are to be seen on the narrow part of the small headland called the Gurnard’s Head in the parish of Zennor. At its eastern end is a large slab, said by some to be the altar-stone, under which, according to another tradition, certain drowned mariners lie buried. At the beginning of the present century it was still the custom to make a pilgrimage to this spot on the parochial feast-day.

VIII. The MS. collections of Dr. Borlase, quoting from the Exeter Episcopal Registers, mention ‘the Chapel of Saint Ante alias Ansa, prope ripam maris,’ under the year 1495, at Saint Ives, in which a guild or fraternity was established, and say that it was turned into a smith’s shop in June, 1770.

IX. A chapel mentioned by Lysons as having existed at the Chapel Field in the Barton of Kerrow and Cornelloe, Zennor.

X., XI., XII. To these we must add, on the authority of Blight (‘Cornish Crosses’), similar chapels at Trewanack, Rose-an-crowz and Chapel Anjou, in Lelant.

These ancient fanes, and others in various parts of Cornwall, bear a strong likeness to each other in their size, shape and mode of construction, and seem to have been built in the earliest Christian period of our country’s history.

Crosses.

To the same period are to be ascribed the most ancient of the wayside crosses for which Cornwall is renowned. These are all of granite, and the oldest of them are extremely simple in form. The following are the examples in the Saint Ives district:

I. Penbeagle Cross, at the corner where the Zennor road is joined by the lane from Penbeagle farm (locally ‘town’). This cross is badly mutilated, a very large portion being broken off. The face has been marked with a small Latin cross roughly incised, and a reversed B appears on the back. This cross was whitewashed over in September, 1890. Here also are the Prior Field and Park Venton (the ‘well-field’). Possibly there was a chapel there. I noticed a holy-water stoup built into a shed at Hellesvean, hard by.

II. A cross at the corner of a hedge (which in Cornwall means a dry-stone wall) bordering the Saint Ives road, in Lelant village. Its round head bears a Latin cross in relief, which some un-enlightened restorer has recently marked out with a coating of tar.

III. A tall, round-headed cross in the new Lelant cemetery, close to the churchyard. It bears a rudely-carved crucifix. This venerable monument formerly stood by the side of the highroad to Saint Ives, where it received rough treatment from the Saint Ives fishermen who came to Lelant to paint their boats. Hence its removal to its present position.

IV. A cross pattee fitchee, carved on a round-headed shaft, in Lelant cemetery; on the other side is carved a crucifix.

V. A plain St. Andrew’s cross carved on a round-headed shaft, in Lelant churchyard.

VI. The round head of a cross, on a wall opposite the Praed Arms Inn, in Lelant village.

VII. A cross at Brunnion in Lelant, marking the site of an ancient chapel.

VIII., IX. The round heads of two crosses, now placed upon the grace of the Rev. William Borlase, the late vicar, in the churchyard of Zennor.

X. A round-headed cross discovered in the wall of a house at Towednack church-town about four years ago; now i the garden at Tredorwin.

XI. Saint Ives Cross, described in our chapter on the church.

XII. A round-headed granite cross built into a hedge on the highroad near higher Trenoweth, Lelant.

Carn Crowze (‘the cross rock’), a spot near the point of the Island is so called from a cross which formerly stood there. There was also a cross in the ancient earthworks on the top of Carn Trencrom.

Holy Wells.

It is not our place to say more about these in general than that they were probably considered sacred long before they became connected with the traditions of Christianity. It was the policy of the early missionaries to give a Christian character to the ancient stones and springs, by identifying the latter with Christian ideas and surmounting the former with the symbol of our redemption, thus directing to the faith of the Gospel that awe and veneration which had been implanted in the minds of the people by the Druids, and which the Christian priests were unable to eradicate. These wells (in Cornish ‘venton’) are the following, in the Saint Ives district:

I. Venton Eia (Saint Eia’s or Ia’s well), on the cliff under the village of Ayr, overlooking Porthmeor. This ancient well, associated with the memory of the patron saint of the town, was formerly held in high reverence. Entries occur in the borough records of sums paid for cleansing and repairing it, under 1668–9, 1680–1, and 1692–3. On the last of these occasions the well was covered, faced, and floored with hewn granite blocks in two compartments. It is still known as ‘the wishing-well,’ from the old custom of divination by crooked pins dropped into the water. For some years past, however, this ancient source of purity has been shamefully outraged by contact with all that is foul. Close to it is a cluster of sties, known as ‘Pigs’ Town,’ and the well has become the receptacle for stinking fish and all kinds of offal. Just above it are the walls of the new cemetery. All veneration for this spot, so dear to countless generations of our forefathers, seems to have departed.

II. Venton Dovey, in the town of Saint Ives. I have not been able to discover who the Dovey is, after whom this well is called; indeed, there is a difficulty even in identifying its site, for although the name occurs in a deed of 1808, I have not met with any person who can remember it. It was perhaps the spring situate at the north side of Shute Street, which, together with the present Dove Street, formed originally one thoroughfare known as Street-an-Poll (Pool Street). Some cottages at the top of the Stennack form a hamlet known as Nanjivvey, or St. Jivvey, perhaps a form of ‘Dovey’; and there is a well hard by.

III. Venton Vigean, referred to in a deed of 1808. I cannot explain the name; it was situate at Ayr, where there is a field which is still called Venton Vision.

IV. Venton Uny (the Well of Saint Ewinus, the saint to whom the parish of Uny Lelant owes its name). This well is most picturesquely situated on the cliff at Hawke’s Point; its popular appellation is Venton Looly. It is still used by romantic young people as a wishing-well.

Dr. Borlase severely says:

‘The vulgar Cornish have a great deal of this folly still remaining; and there is scarce a parish-well, which is not frequented at some particular times for information, whether they shall be fortunate or unfortunate; whether, and how, they shall recover lost goods, and the like; and from several trials they make upon the well-water, they go away fully satisfied for a while; those who are too curious being always too credulous.’

Webmaster

Webmaster