The Parish Church of Saint Ives.

For a long period the inhabitants of the Chapelries (as they then were) of Saint Ives and Towednack laboured under serious inconveniences, owing to their being so far from their parish church, which was the church of Lelant. So long, indeed, as Saint Ives was merely a small village composed of a few fishermen’s huts, this hardship had to be borne. But at the commencement of the fifteenth century Saint Ives had become rather an important and populous town, being, in fact a foremost port of communication with Ireland and Brittany. Resolving, therefore, to remedy this inconvenience, and at the same time to improve the status of the town,

‘the inhabitants’ (says Hicks) ‘did about the year 1408 petition the Lord Champernon, Lord of Saint Ives, that he would be pleased to petition His Holiness the Pope to grant his license for a chapel to be built within the borough; so the Lord Champernonon petition did obtain from His Holiness the Pope Alexander the 5th, primo anno pontificatus anno gr. Dni 1410, his bull to build a chapel in the borough; and likewise obtained a license from the Most Reverand Father in God the Archbishop of Canterbury, and a license from the Right Reverend the Bishop of Exeter, for the building of the said chapel, which, together with the tower, was begun in the reign of King Henry V., and finished in the reign of King Henry VI., being 16½ years in building.’

Hicks, and all historians who have followed him, make a mistake in naming 1410 as the date of the papal bull. If the Pope referred to was Alexander V., it must have been 1409, the year both of the election and of the death of that pontiff. In giving these facts, Hicks evidently had before him the original papal license, which in his time was preserved among the borough archives; and it is more probable that he was mistaken in the date than in the Pope’s name.

Gilbert quotes from the text of the petition presented by the inhabitants to the Pope, through the medium of the lord of the manor, the following passage, giving the reasons urged by the Saint Ives people for their desiring a separate parish church:

‘As it had pleased the Almighty God to increase the town inhabitants and to send down temporal blessings most plentifully among them, the people, to show their thankfullness for the same, did resolve to build a chapel in Saint Ives, they having no house in the town, wherein public prayers and Divine service was read, but were forced every Sunday and holy day to go to Lelant church being three miles distant from Saint Ives, to hear the same, and likewise to carry their children to Lelant to be baptised, their dead to be there buried, to go there to be married, and their women to be churched.’

ST. IVES CHURCH FROM THE N. E.

Accordingly Pope Alexander V., on October 20, 1409, and (after the death of the last-named pontiff) his successor, Pope John XXIII., on November 18, 1410, recommended Bishop Stafford of Exeter, in whose diocese Cornwall was, to make

‘the chapels of S. Tewynnoc and S. Ya parochial, with font and cemetery, but dependent on Lelant.’

The Index to the Ancient Episcopal Registers of the Diocese of Exeter, lately published with notes and translations, by Prebendary Hingeston-Randolph, supplies us with the following extract from Bishop Stafford’s register, under the date September 27, 1409:

‘Lelant. Chaples of St. Tewennoc the Confessor, and St. Ya the Virgin. Peter Pencors, William Stabba, James Tregethes, John Guvan, and other parishioners of the said chapelries, complained that they lived, for the most part, four, three, or (at least) two miles from the Mother Church of Lelant, the roads being mountainous and rocky, and liable in winter, to sudden inundations, so that they could not safely attend Divine Service, or send their children to be baptised, their wives to be churched, or their dead to be buried; the children often went unbaptised, and the sick were deprived of the last Sacraments. They stated thatthey had built the two chapels above-named at their own expense and had enclosed suitable cemeteries, to be sufficiently endowed for two priests to serve therein, and they prayed the Bishop to consecrate the same; who accordingly commissioned Richard Hals and John Gorewyll to meet all the parties (including specially John Clerk, the Vicar of Lelant), and to enquire and report.

‘Bulls of Pope Alexander V. and of Pope John XXIII., for the dedication of the dependent chapels of St. Tewinnoc and St. Ya; presented to the Bishop, in the chapel of his palace at Exeter, 8 Sept. 1411, by two parishioners thereof, viz., Peter Pencors and John Guvan, who asked him to give effect thereto. They told him of the difficulties above recited, complaining that they were obliged to repair the parish church for the baptism of their children, to receive the Sacraments, and to bury their dead; that occasionally some of them were unable to undertake such a journey, and some were left to die without confession and the last rites of the Church, to the great loss of their souls. Accordingly they desired that fonts may be placed in these chapels and the Sacraments administered therein; also that the cemeteries should be licenced for interments. Inquiry was ordered; the petition to be granted if the result were satisfactory. Both Bulls are given in full; and in the second, reference is made to a contention between these parishioners and John the Vicar of Lelant. The Bishop forthwith directed the Precentor and the Chapter of Crediton (Rectors of Lelant) and the said Vicar to appear before him personally, together with any others concerned, in the Church of Crediton. But the Bishop shortly afterwards started on a visitation-tour in Cornwall, and, reaching Lelant of the 9th of October, he met the parties there, and granted his licence to celebrate Mass in the said Chapels.’

So soon as the requisite authority had thus been obtained, the people of Saint Ives set about building (on the site of the humble oratory, and the chapel which succeeded it) a church which should be worthy of their newly-acquired privilege. In this our common-place age, we can scarcely for a notion of the immense importance with which such an event was then regarded. No pains were thought too great to be undertaken, no expense too heavy to be borne, to make the work a complete success in every respect. In the Middle Ages every capable parishioner was expected to contribute to the undertaking either in work or in money. The mason gave his labour, the artist his skill, and the husbandman lent his beasts of burden.

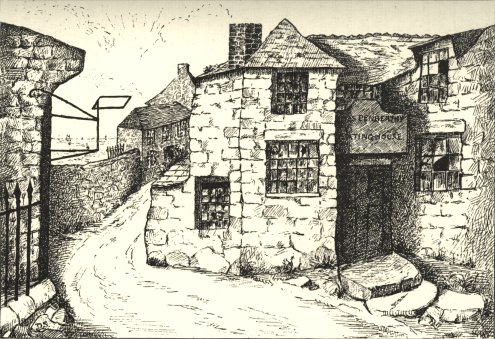

THE OLD PARSONAGE.

A local tradition will have it that the granite used in the construction of Saint Ives Church was brought by water from Zennor, and that the boats often had to wait for weeks for weather sufficiently calm. Everything we know bears out this legend; roads at that date West Cornwall could not be said to possess, unless mere bridle-tracks were entitled to the designation. As a natural consequence, wheeled vehicles were unknown, pack-mules being then, and for long after, the only medium for the conveyance of goods by land. The wild highland parish of Zennor was famous for the excelent quality of its granite, which then, as now, was probably the only commodity largely exported from that remote region.

The site of the church being very near the shore, the labour required for bringing the materials would, by their conveyance in boats, be reduced to a minimum. It must not be supposed, however, that the sea then came right up to the churchyard, as it does now. In the seventeenth century ‘there was a field between the churchyard wall and Porth Cocking rock, and sheep grazed on it,’ as an old man informed Mr. Hicks.

Some of the workmen engaged in building the church lived, during the time of their being so employed, in a house which is still standing opposite the south porch. It was afterwards used as the presbytery or parsonage. It is a rambling old building, and the front-door a few years ago still had its pointed archway. A prominent corner of the church-porch, immediately opposite this house, has been flattened off, as though to leave room in the road between—a circumstance which rather supports the tradition that the house was standing before the church was built. This building reminds one of the ‘church houses’ of South Wales, where they are the inseparable adjuncts of the parish churches.

It may be convenient to state here that we have only been able to recover the names of two of the priests in charge of Saint Ives before the Reformation, viz., John Hycks, and one whose surname was Pentreth. They were chaplains (or curates) here in 1520.

The church was completed in the year 1426, having been sixteen years and a half in building. It was not, however, consecrated until a few years later.

Webmaster

Webmaster