The following essay appears as a supplement to Blight’s Churches of West Cornwall [Blight 1885]. The text was probably prepared for the Gentleman’s Magazine 1864 and must be read in the context of that date. The drawings are by the author.

| First Page | Previous Page | Next Page |

IN compliance with an invitation from the Royal Institution of Cornwall, the meeting of the Cambrian Archæological Association in 1862 was held at Truro, whence excursions were made to different parts of the county.

The members arrived at Truro on Monday, August 25th, and the two following days were devoted to the neighbourhoods of Bodmin and Truro. On Thursday a large party left for Penzance. Every facility was kindly offered by the directors of the West Cornwall Railway. The weather could not possibly have been finer; and it is only to be regretted that more time was not available for the examination of the numerous antiquities scattered within a radius of five or six miles around the town.

Trembath Cross.

A few of the members proceeded by the first morning train to the Marazion station, visiting St. Michael’s Mount, and the inscribed stones at St. Hilary. The greater number, however, came on by the next train, joining the others at Penzance, where carriages were waiting to drive westward.

After leaving the outskirts of the town, the first object noticed by the wayside was the ancient cross at Trembath.

It is of the usual form of the Cornish cross, a plain shaft with a rounded head, but differs from any other in the county in the rude figures incised on two of its sides. On the eastern face is a patriarchal cross. Possibly it may have marked the boundary of land of, or have been in some other way connected with, a religious Order holding land in the neighbourhood. The canons regular of the Order of the Holy Sepulchre, for instance, bore on the cassock a cross of similar form.

Boscawen-ûn Circle.

At Drift, about a mile beyond this cross, we passed the two pillars described and figured by Borlase (“Antiquities of Cornwall,” p. 187), and soon after the tall Tregonebris stone was seen. We did not, however, alight from the carriages to inspect those objects, as better examples of monuments of this class were to be visited in the course of the day. We had now advanced about six miles on the Land’s End road, and were opposite the Boscawen-ûn Circle, which lay in a moor on the left, a quarter of a mile distant. Nearly all the party went to inspect this remarkable circle, which is formed by nineteen stones, averaging little more than three feet in height, and placed at irregular distances, some being thirteen feet apart, others no more than seven or eight. Within the area, but not in the centre, is a stone nine feet long, in an inclining position. It inclines W.S.W. 49° from the horizon, but whether originally upright is uncertain. No other stone circle in Cornwall has this peculiarity, which is found, however, in the tall stones in the “ship-barrows” of Sweden, and marks probably the site of some structural arrangement.

The diameter from east to west is seventy-six feet, from north to south eighty-one feet. Dr. Borlase speaks of a cromlech on the north-eastern side. This does not now exist; but a large stone lies near the spot, and may have formed a side or covering for a kist-vaen.

It is unnecessary here to give the numerous speculations as to the use of this Circle, but it may not be out of place to say that the late Rev. Thomas Price considered this to be the Circle mentioned in an ancient Welsh triad, whatever importance may be attached to it, as “the Gorsedd of Boscawen in Damnonium.”

About thirty yards south-east of the Circle is a barrow from six to seven feet high.

At the time of our visit the Boscawen-ûn Circle was divided by a hedge, and many of the stones were overgrown by brambles and furze. Recently, however, these disfigurements and obstructions have been cleared away. The Circle has been enclosed within a strong fence, and is now secure from accidental or wilful mutilation. For this care taken of a valuable monument of a remote age, the county owes a debt of gratitude to Miss Elizabeth Carne, of Penzance, on whose property the Circle stands, and who has thus set an excellent example to Cornish landholders to preserve those antiquities for which the county is so justly celebrated, but which are in too many instances liable to destruction by thoughtless and ignorant tenants a.

After a pleasant scramble through heath and gorse, we regained the carriages on the high road, and proceeded direct to the Land’s End. The cross at Crowz-an-wra was glanced at as we drove along. On the right were the hills of Chapel Cam Brea and Bartiné. An open country of cultivated fields, amidst tracts of moor and down, lay spread on the left and before us, until the long line of the distant horizon became visible, and approaching the cliffs we were soon as far westward as it was possible to go on England’s soil.

St. Sennen Church.

It was scarcely archæological to pass St. Sennen’s Church unheeded, but there was a long day’s work before us; we had left Penzance an hour later than was originally intended, and as many of the company had never before visited the Land’s End this was considered a favourable opportunity. Moreover, on the green turf lay spread white cloths bearing almost every kind of refreshment that could be brought to such a spot. This handsome luncheon had been provided by gentlemen of the neighbourhood, and as it was now near mid-day a halt of this sort was not unacceptable, for many had left Truro so early as six o’clock.

Here, on the dark cliffs of Bolerium, the British “Penrhyn Guard,” the “promontory of blood,” were assembled representatives of the Celtic races from Scotland, Wales, and Ireland, met on Cornish ground to investigate the monuments erected by their common forefathers centuries ago, erected in the ordinary course of a simple mode of life, by men little dreaming of a future in which the meaning of their cromlechs, tolmens, and circles could possibly become subjects for earnest controversy,—when the stones which they rudely heaped together to meet their commonest wants, and which are now the sole testimonies of their existence, should be regarded as objects of mystery,—when the greatest deeds of their best men should be forgotten, and not the name of one remembered.

The Land’s End could not have been seen to greater advantage. There was a clear, bright sky overhead; the sun sent down cheering rays; the Atlantic was stretched out before us; the deep-blue waves were not angry, but they are never at rest; and the cliff-base and jutting rocks were fringed with snow-white foam. The old Longships looked as firm as ever, and we could see the cloud-like islands of Scilly breaking the line of the distant horizon. The company consisted of about a hundred, for many ladies and gentlemen from Penzance and neighbourhood had joined this day’s excursion.

Section of Pier,

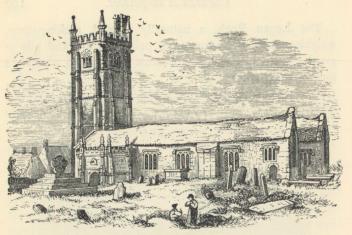

St. Sennen Church.

Leaving the Land’s End, we again passed near St. Sennen’s Church, but there was no time to enter it. It is a small, unattractive structure of the fifteenth century, interesting chiefly on account of an inscription on the stone at the base of the font, which, in the letters and with the usual abbreviations of the period, tells that “This church was dedicated on the festival of the Beheading of St. John the Baptist, A.D. 1441,” and thus affording direct evidence of the date of the greater portion of the building; for it is not improbable that the walls of the chancel may have been erected long before. It was not unusual to re-dedicate a church when rebuilt or restored. The fifteenth-century piers shew much judgment in the use of that intractable granite; each presents a section of a square with three-quarter round shafts attached.

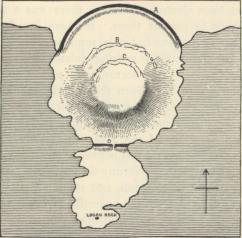

Plan of Castle Treryn.

About three o’clock we had arrived at the quaint old village of Treryn, and thence proceeded to the cliffs to examine the “castle” and the Logan Rock. This promontory was strongly fortified: three lines of circumvallation may still be traced. First, there is a broad ditch, A on the opposite plan, from the bottom of which to the summit of the first vallum of earth is about twelve feet. The second and third lines, B, C, appear to have been formed of masses of rock and earth, combined with the natural inequalities of the ground. They all extended to the sides of the cliffs as far as they were necessary; the cliffs themselves forming impenetrable barriers on the sea side. At D is another ditch cut across a narrow isthmus, and a straight light of defence exhibiting rude masonry. These are the remains of the finest cliff-castle in Cornwall, perhaps in England. Such structures were numerous on the coast of the Land’s End district; almost every promontory was cut off in like manner. It is unnecessary to repeat all the theories respecting their origin and use. Many have supposed them to be the works of the Danes, or other invading foes, who may have drawn up their ships in some sheltered cove hard by, fortified these promontories, and so gained a footing on the land, whereby they might at least so far subjugate the natives as to be able to procure for themselves necessary provisions. Before accepting this theory, however, it should be remembered that in many instances there are no landing-places near these fortifications, no sheltered coves in which to draw up boats, and the cliffs are altogether inaccessible. Supposing it possible for foreigners to have effected a landing and remained undisturbed sufficiently long to have constructed these fortifications, in all probability they would soon have been at the mercy of the natives. If shut up within their lines of defence their vessels could soon have been destroyed, unless there was a sufficient force without to protect them. If these invaders could not have been overcome in battle, supplies could have been withheld by the natives retiring inland with all their property. Indeed, there seems more reason to suppose these structures to have been the last strongholds of the natives themselves, driven seaward before a stronger race advancing on them from the east. The Rev. James Graves, the learned Secretary of the Kilkenny Archæological Society, who was present on this occasion, remarked at a subsequent meeting of the Kilkenny Society, that “The stone forts, cromlechs, caves, tumuli, and stone hut circles of the aborigines were alike in both countries (Ireland and Cornwall); but what chiefly attracted his attention was the fact that they were found clustered on the western hills and cliffs of England, just as we find them abounding on the western mountain sides and cliffs of Ireland. His impression was that the race which built them and fought in defence of them were a race fighting against an exterminating enemy; that they were unsuccessful; next found shelter in Ireland for a time, and were at last hurled over the cliffs of Kerry and Arran into the Atlantic. He defied any one to stand on the Cornish and the Kerry hills and not have the same idea forced on him.” If the cliff-castles were the works of foreigners, it seems evident they must have been thorough masters of this part of the country.

The Logan Rock, a naturally formed rocking-stone, weighing above sixty tons, and poised on a grand pile of granite, was examined with interest by those to whom the locality was new.

St. Levan’s Church.

Before the carriages had reached Treryn, a few members branched off to see St. Levan’s Church. It has features worthy of notice, but it was found impossible to include it among the objects to be visited in the day’s excursion.

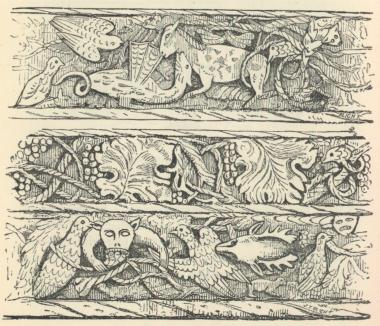

At St. Burian we had half-an-hour to examine the church, a large building of the fifteenth century. Remains of an earlier structure, however, exist in the chancel, which has in its north wall a Norman arch and pier with respond. The arch is built up, and the greater portion of the pier is buried in the masonry at the junction of the chancel with the east wall of the north aisle, but both are still distinctly to be seen. The elaborately carved and painted roodbeam was much admired. The cross in the churchyard was not considered of very early date. Possibly it may be of the thirteenth or fourteenth century.

St. Burian Church.

Roodscreen, St. Burian.

From St. Burian our route took a south-easterly course, passing on the road the Sanctuary cross. It is of the Latin form, and has the figure of our Lord dressed in a kilt carved in relief on one side. It still stands in the original socket-base, but a portion of the shaft has evidently been broken away. A quarter of a mile from this cross, beside a little stream on the farm of Bosliven, are the remains of an ancient structure called the Sanctuary. Athelstan is said to have founded the collegiate church of St. Burian, and to have granted to it the privilege of sanctuary. These ruins have been supposed to occupy the site of the original structure, but they are most probably no more than the walls of an oratory or chapel: buildings of this kind were numerous throughout Cornwall. It should be stated, however, that glebe lands had often, anciently, the privilege of sanctuary b. The people of the neighbourhood speak of the spot as the “Sentry.” When I first went to see it no one could direct me to the “Sanctuary,” but the site of the “Sentry” was well known. A correspondent of the Gentleman’s Magazine in 1781, after offering a few remarks on certain peculiarities in Cornish Churches, goes on to say:—

“I might add at the same time another circumstance which seems to me peculiar to the churches of Cornwall. There is in most parishes of this county a field (generally near the churchyard) which is commonly called the sentry (perhaps sanctuary), but this field is not always glebe land, or at least has been filched from the church in some instances. How came this name to he given to one field only in a parish? and why is not this field always glebe land?” In reference to the word sentry, the editor adds in a foot-note, “Probably cemetery (or burying ground), as the old cemetery-gate at Canterbury is called by corruption centry-gate.”—(Vol. ii. p. 305.)

This enquiry of the correspondent of 1781 deserves more attention from Cornish archæologists than it appears to have received at the time. I have recently been informed that the two fields which constitute the glebe of St. Feock are known as the “Sentries” and the name is still probably retained in other parts of the county.

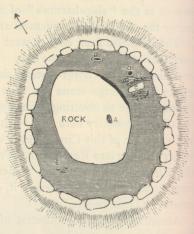

Plan of Barrow,

near Boscawen-ûn Circle.

(a) In anticipation of a visit, in the autumn of 1864, from the members of the Royal Institution of Cornwall and of the Penzance Natural History and Antiquarian Society, trenches had been Cut within the Circle, but nothing of interest appears to have been discovered. The large barrow mentioned above, on being dug into, was considered by those who conducted the operations to have been previously opened. There was found, however, on its north side the remains of a kist-vaen, and nearer its centre, in a line, three circular pits, each about one foot in diameter, and covered with flat stones. Two only contained ashes.

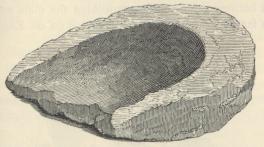

Stone found in a Barrow,

near the Boscawen-ûn Circle.

Urn found in a Barrow,

near the Boscawen-ûn Circle.

A barrow sixty yards south-west from the Circle, on being examined, also shewed signs of being previously opened. Its construction is remarkable, consisting of a circle of stones set around a large granite rock, twelve feet by eleven feet, and two feet ten inches thick, with a smooth upper surface in which is sunk a cavity, A, one foot six inches in length by one foot one inch as its greatest breadth. This upper part of the rock appears originally to have been exposed to view, though it had become overgrown by vegetation, and formed the summit of the barrow. Between the enclosing circle and the rock is a space with an average breadth of four feet, in which were found, at B, at the depth of eighteen inches, a piece of granite, eighteen inches in length by twelve inches in breadth, and about nine inches thick, scooped out on one side to the depth of four inches. It is but the fragment of some instrument, for evidently the stone has been broken across. The surface of the hollowed part appears to have been subjected to friction, as if a muller had been worked in it for the purpose of bruising or grinding grain *. At C, a stone two feet six inches long and about the same breadth, set on its edge, and rising nearly to the surface of the barrow; on its south side were a number of small loose stones; on the north side many calcined human bones, fragments of large urns, and a small one entire, mouth downwards, filled with soil. It measures in height four and a-half inches, in diameter at top three and a-half inches. Around the upper part is a very rude ornamentation, formed by the usual mode of dotting in lines with some pointed instrument, perhaps the end of a stick or a sharpened stone. At unequal distances the more numerous lines are crossed, but so carelessly as scarcely to form a regular pattern. Although of inferior workmanship, this little urn may be regarded with much interest on account of the locality in which it was found. By the kind permission of Miss Elizabeth Carne I am enabled to present the accompanying figure (see p. 191). Fragments of pottery also occurred at E, on the south-west side. The large rock with the cavity has long been known to the people of the neighbourhood as the “Money Rock.”

(b) See Dr. Petrie’s Ecclesiastical Architecture of Ireland, &c.

(*) I recently found a rude granite mortar, the very counterpart of the above, in an ancient circular work in the neighbouring parish of St. Paul.

| First Page | Previous Page | Next Page |