The following description is lifted directly from [Quiller-Couch 1898] from an article written by Thurston C. Peter entitled “The Collegiate Church of St. Buryan.” It must be read in the context of that date. The contemporary photographs are by J. C. Burrow, F. G. S. and were printed with the original article.

| First Page | Previous Page | Next Page |

ST. BURYAN FROM NORTH-WEST

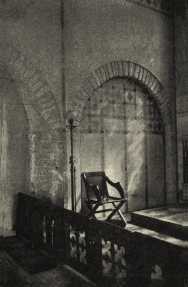

ST. BURYAN is one of the most interesting churches in West Cornwall, both architecturally and historically. The church, as we see it to-day, is for the most part of the fifteenth century, but portions of it are probably later even than that, and should perhaps be dated in the second half of the sixteenth. But there is an exception to this late date in a portion of the north wall of the chancel, where a rude semicircular arch, set in rubble masonry and enclosing a smaller arch, is at least three centuries earlier in date. Within, the larger arch alone is visible, and not only is it interesting in form, but also from the fact that the voussoirs of the arch are not of stone but of concrete made of the shell-sand of the neighbourhood. This interesting arch was only discovered in the progress of the restoration. The church consists of a nave 58 ft. in length, a chancel 43 ft. long, and two aisles, which, like the nave and chancel, are each 14½ ft. wide, and extend the whole length of the church to within a few feet of the east wall of the chancel. The unusual length of the chancel is, of course, due to the collegiate character of the establishment, and the consequently considerable number of clerics who had to be accommodated; though, if we credit Leland, the provision was unnecessary, at any rate in later times: ‘There longeth,’ says he, ‘to S. Buryens a deane and a few prebendarys that almost be nether ther.’ As we approach the church from the south, the first object that catches our attention is a cross in the open space outside the gate, and round which bodies have been found buried, suggesting that it was formerly within the consecrated enclosure. And in the churchyard itself is another, of which only the head remains, which was fixed, after the removal of the shaft, on the top of the four steps which constitute the base. It is of much beauty and interest, having the figure of our Lord on one side, and on the other five bosses, typical of the five wounds of Christ. Just behind this is the porch, of a type very common in West Cornwall, buttressed and battlemented and with crocketed pinnacles to the buttresses, of which that at St. Just (in Penwith) appears to be a copy, and perhaps the work of the same man. The windows on the south side are each of three lights with depressed rounded heads, and surmounted with square hood-moulds. Between the second and third windows east from the porch is an octagonal projection containing the stairs that formerly led to the rood-loft. The oak rood-screen, judging from the fragments that still remain, must have been an object of singular beauty, rich with crisp carving and exquisite colouring. In 1814 the church was repaired, and the screen (as well as some carved pew ends) was destroyed — the screen being sacrificed (it is said) because the vicar had a weak voice, with which he thought it interfered.

ST. BURYAN,

NORTH WALL OF CHANCEL

ST. BURYAN, SOUTH PORCH

ST. BURYAN, INTERIOR

ST. BURYAN, MISERERE STALLS

(Clarice the wife of Geoffrey de Bolleit lies here, God on her soul have mercy: who pray for her soul shall have ten days of pardon.) What a glimpse into the old world! Here in Norman-French, written some 700 years ago, we are promised ten days pardon if we will but pray for mercy on the soul of Clarice. We can all honestly pray for her if she any longer needs it, whether induced thereto by the promised pardon, or merely by a feeling that more things are wrought by prayer than this world dreams of. Hals in his ‘Parochial History’ tells us that this stone was discovered by the sexton, about 1665, while digging a grave.

1 During the restoration a lead coffin, but without contents or inscription, was found here, and this, too, local fancy has seized on as the former holder of the royal bones!

2 Also called Trethin and Tirthney.

OF the saint who gives the church her name we really know nothing, except that she was a king’s daughter, and in the fifth century dwelt here, and here built an oratory.3 At the same time it is not improbable that she is the same person as ‘Bruinsech the Slender,’ commemorated in the Martyrology of Donegal under May 29, the day that in an English Martyrology of 1608 is set down as St. Buryan’s feast, though this is now held on the nearest Sunday to May 12. Colgan (‘Acta Sanctorurn Hiberniæ,’ vol. i) conjectures that she can also be identified with Bruinecha, one of the holy women who lived with the mother of St. Piran. Dymna, the chief of Hua Fiack, admired her beauty and carried her off to his castle by force. Piran then went to the castle to demand back his sister (for his mother had adopted her), but the savage chief refused, unless, as he said sneeringly, he should be awaked from sleep next morning by a swan — a thing he deemed impossible, it being then the depth of winter. Holy Piran and his comrades stood around the castle all night, and shortly snow began to fall and covered the whole ground except where these holy men were posted. As morning broke, it was seen that a miracle had been wrought, for there on every roof and turret of the castle was perched a swan whose plaintive cries aroused the inmates. Beside himself with fear, the chief craved pardon of the saint and let the lovely Bruinecha free. Lust, however, was too strong for him; his heart was hardened, like Pharaoh’s of old, and in a few days he was seeking her again; but at the news of his approach the lady died. Shocked by this, the chief turned over a new leaf and showed such genuine signs of repentance that Piran, feeling he might be trusted, by prayer restored the lady to life. The story suggests Juliet and Friar Laurence; but, as we are dealing with the doings of saints, related for our edification by other saints, it is safest to believe the story as it has come down to us. The Cornish tradition that Buryan was one of Piran’s companions to this shore is consistent with the identity of Buryan and Bruinecha. Tradition tells us nothing of her life in this county, except that it was one of holy benevolence. How many noble men and noble women pass from us every year in the same way, forgotten except for a dim tradition of holiness and kindness, while persons of less worth but greater ‘splash’ have pretentious monuments erected to their memory!

About a mile or so south-east of the church is a little spot called ‘The Sanctuary,’ on the farm of Bosliven, and here by the side of a gently running brook are still visible the remains of what may possibly have been a small oratory. It is far from improbable that this is the place where once lay the mortal remains of St. Buryan, at whose shrine it was that Athelstan, in A.D. 939, vowed that, if successful in his contemplated conquest of the Scilly Islands, he would, on his return, found here a college of priests as an act of gratitude to God.

3 A hospital bearing the names of St. Buriana and St. Alexis was founded at Exeter in 1164 (Reynolds, Anc. Dio. of Exeter, p. 166).

| First Page | Previous Page | Next Page |