TOWEDNACK CHURCH.

The parish of Towednack is only less wild than Zennor, and its ‘church-town’ (i.e. village round the parish church) consists of two farmhouses and an inn. Towednack church, says Blight, is remarkable as alone possessing a chancel-arch among the churches of West Cornwall; this arch is of the thirteenth century, very acutely pointed, and consists simply of two chamfered orders springing from corbels. The church consists of chancel, nave with western tower, and south aisle and porch; the two latter are much later than the other parts. The tower, of granite, very low and massive, is altogether unlike every other in the district, and being constructed without any attempt at ornamentation, proper use was made of the material at hand. The string-course and cornice are remarkably bold; the battlemented parapet (walled in on the east and west sides) is of the simplest character. The belfry lights are square-headed and chamfered; altogether it is a characteristic structure, harmonizing well with its site, in the midst of a most wild and dreary region. The tower staircase, on an unusual plan, is constructed without newel or winders, and has its entrance direct from the north-west angle of the nave. The tower-arch appears to have been originally, like most others of the same date in Cornwall, a plain soffit-arch; to this responds and a chamfered order have been added. A portion of the old impost-moulding remains, and just inside the arch are two boldly-carved corbels. The springing of the tower-arch is peculiar as being quite a foot back from the face of the columns. The eastern bench in the porch is formed of a block of granite, seven feet long, one foot six inches high and ten inches wide, with an incised double cross. ‘This stone evidently does not occupy its original position; it differs from the ordinary types of the Cornish churchyard and wayside cross, and is most probably an early Christian sepulchral monument’ (Blight).

On the 27th June, 1542, Bishop Vesey of Exeter directed his suffragan, William of Hippo, to consecrate the cemetery of the parish church of Towednack.*

There are two old bench-end in this church, each carved with a medallion profile portrait of a man in a hat, with moustachios and beard; on one is inscribed, in letters curiously inter-laced, ‘Master Mathew Trenwith warden,’ and on the other, ‘James Trewhela warden.’ Both bench-ends, which bear the date 1633, have been worked into a chancel-seat, and are suffering severely from damp. ‘The remnant of the chancel-screen is of the same age as the bench-ends,’ says Blight [this book mentions neither screen nor benchends? ed.].

The font is ancient and simple in form, but was carved in the last century. The upper portion of the bowl is divided into square panels, two of which contain respectively the Latin initials I. R. and W. B.; the other compartments exhibit two quatrefoils, a conventional lily and the date 1720, while another is left blank. The round base of the column and the pedestal meet in a tooth pattern at the joint. On the bowl is an early carving of a face in bold relief.

In the belfry is a mediaeval bell, bearing the inscription ‘Sancti Spiritus assit nobis gracia’ (May the grace of the Holy Spirit be with us). There is a credence on the gospel side of the high-altar space, and a piscina on the epistle side. Also a support for the rood-loft remains, on the south side of the chancel arch.

Over the door of the porch is a small sundial, bearing the following inscription: ‘1720. Bright Sol and Luna Time and Tide doth hold. Chronodix Humbrale.’ [This should probably read "Chronodix Inumbrate"]

In the north wall is a blocked doorway with a plain and very massive tympanum of granite.

Inside the church, on the south wall, is a marble slab inscribed in memory of Thomas Rosewall of Hellesvear, Saint Ives, Esquire, who died 1841 aged 87. Also of Mary his wife who died 1829 aged 72. Also James, Thomas and Juliana Rosewall, of Talland, Saint Ives.

At a meeting of the Penzance Natural History and Antiquarian Society held in November 1886, Mr. J. B. Cornish mentioned that, during the taking down the chimney of an old house close to Towednack church recently, an ancient cross was discovered in the ruins, and was put up in a garden at Tredorwin about a mile from the church. It is of granite, about three feet high, with rudely cut circular stem and top.

There is an unpleasant and probably erroneous tradition that the bodies in Towednack churchyard, which is very small, after having lain there for twenty years, were disinterred to make way for fresh burials, and stowed away in a charnel-house.

There is an old legend that, ‘when the masons were building the tower of this church, the devil came every night and carried off the pinnacles and battlements. Again and again this work was renewed during the day, and as often was it removed during the night, until at length the builders gave up the work in despair.’ Associated with this tower is a proverb: ‘There are no cuckolds in Towednack, because there are no horns on the church-tower’ (See Hunt, ‘Popular Romances’). Perhaps this is not unconnected with the celebrated Towednack ‘Cuckoo Feast,’ noticed in another chapter of our history.

The Parish Registers go back to 1676, if we include a copy of an early volume, long since lost, which copy was made by Dr. Cardew. One of the first entries is: ‘1676. Baptised Anne, daughter of Andrew Rosewall.’

Among the peculiar names occurring in this register are those of ‘Emlyn Baragwanath,’ buried 1684, and ‘Duence Battrall,’ buried in 1747.

Tombstones in Towednack churchyard. East of the church.

William Rosewall yeoman, of Lower Bussow in this parish; died 1864 aged 50. Also Jane his wife; and William their son who died 1868.

Amy wife of John Chellew and third daughter of John Quick of Chytodden in this parish; died 1874 aged 63.

William Quick of Buzzow in this parish, yeoman; died 1842 aged 81.

‘In Memory of the Quick family of Trevalgen, St Ives.’ Peter B. Quick, died 1853 aged 71. Richard Quick died 1855 aged 72. William Quick died 1855 aged 67.

Elizabeth Reynolds of Trevessa Wartha in this parish; died 1850 aged 77. And others of the family.

Elizabeth wife of John Green, Clerk of this Parish, died 1843 aged 33.

Weep not, my child and husband dear,

I am not dead but sleeping here;

My debt is paid, my grave you see,

Prepare yourselves to follow me.’

Also John Henry their only child, died 1843 aged 5.

John, Thomasin, Elizabeth and Peter, children of Peter and Mary Quick.

Israel Quick junior, of St Ives, died 1825 aged 36. Also Paul his son.

John and Alice Quick, of St Ives, died 1815 aged 13. (Stone vault with broken slate.)

William Berryman, died 1834 aged 44. Also Wilmot his wife. Solomon Richards, died 1857 aged 58.

Christopher Edwards, died 1826 aged 68. Also Margery his wife, and their children Thomas, Ann and Mary, the latter of whom died 1871 aged 77.

Stephen Curnow, died 1837 aged 81. Also his sons John and Andrew. James Quick, died 1859 aged 59.

South of the church.

On the south wall. John Quick of Chytodden in this parish, died 1855 aged 70. Also Elizabeth his wife.

Robert Michell, died 1865 aged 59.

Sampson son of Sampson and Hannah Curnow, died 1865 aged 17.

West of the church.

William Martin of Embla in this parish, died 1865 aged 65.

The new cemetery adjoins the churchyard on this side.

North of the church.

| 3 granite headstones and footstones: |

| G. S., 1791. |

| J. J., 1792. |

| I. O., 1795. |

James Quick, died 1839 aged 74. Also Elizabeth his wife. Lydia Hickes, daughter of Francis and Sarah Hickes of St Ives; died 1804 aged 5.

’The Village Maidens to her grave shall bring

The fragrant Garland each returning spring,

Selected sweets in enblem of the Maid

Who underneath the hollow turf is laid.

Like her they flourish beauteous to ye eye,

Like her too soon they languish fade and die.’

Margaret wife of Richard James, died 1848 aged 48.

ZENNOR CHURCH.

ZENNOR CHURCH.

Zennor church is dedicated to Saint Sinara, virgin. It consists of chancel, nave, western tower, north aisle, south transept and south porch. The south side of the nave is of the thirteenth century, the transept and chancel decorated and contemporaneous. Originally the church was cruciform, but late in the fifteenth (or early in the sixteenth) century the north transept was removed and a north aisle built, extending the entire length of the nave and chancel, into which it opens by an arcade of six rudely constructed arches of unequal span, supported by plain octagonal granite piers. The tower, of the usual Cornish perpendicular type, is constructed of ashlar granite, and has three stages marked by plain set-offs, and a bold string-course above the plinth. The west window is constructed of catacleuse stone from the neighbourhood of Padstow, which retains its sharpness of angle and outline as freshly as when first inserted, affording a striking contrast to the disintegrated granite. Above this window is an ogee-headed niche, which formerly contained an image. The south-east portion of the chancel is of Norman date and older than any other part of the building. Westward of the porch-doorway is a single acutely pointed light, three feet high by six inches in breadth, with a wide splay of three feet three inches through a very thick wall. It was mistaken by Blight, writing before the restoration of 1890, for a round-headed Norman one, but on examination it proved to be a very early lancet window of the thirteenth century. It was in his time partially hidden by a gallery, concerning which the following note was made in a private account book of William Borlase, Vicar of Zennor in 1772:

‘Memo: April 9th 1794. In the year 1772, when the singing-gallery was erected, and previous to the compass-roofing of that part of the church over the gallery, I observed these figures, on one of the oak sills which supported the south part, 1172 or 1177, which I should take to be the date when the church of Zenor was built, so that about the time of the Lincoln Taxation it was more than one hundred years old.’

But there can be no doubt that the vicar read the figures wrongly; they were, probably, 1472.

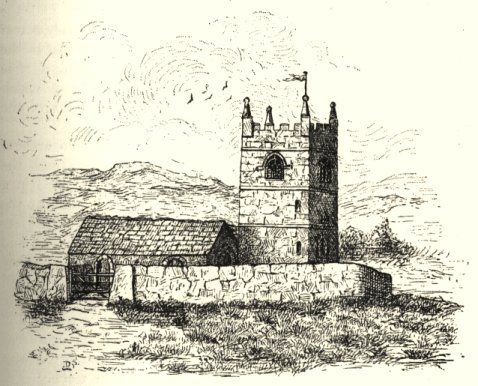

ZENNOR CHURCH, FROM THE N.W., BEFORE THE RESTORATION.

The doorway has been so much affected by modern repairs that it is difficult to decide whether it is contemporaneous with the window.

The chancel is raised one step above the nave, and the sacrarium has two steps, all three extending continuously across the aisle, which, in the lower part of the wall to the height of the window-sill, has masonry projecting eight inches, and a rude bracket of granite, for an image, the upper surface of which measures one foot by one foot two inches. The walls of the aisle were rebuilt about fifty years ago.

The transept probably opened into the nave by two arches; but these, except the springing of the westernmost, with the central pillar, have been removed; the space was spanned by a wooden beam until the restoration. The existing piers at the angles of the transept correspond to the second and fourth piers of the nave arcade; they are indeed of the same character and date, and take the places of others of an earlier period. They are in fact an instalment of a new arcade, showing that it had been intended to remove the south transept also, and substitute an aisle to correspond with the north aisle. The south wall of the transept has an acutely pointed window, with a plain chamfered scoinson arch. Having lost its tracery, it had been fitted with a wooden sash previous to the restoration, when tracery of a geometrical design was inserted. In the south wall of the chancel is a well-restored two-light decorated window, evidently of the same date as the transept window, and a second window of the same design has been inserted. by its side in the blank wall east-ward. In all the earlier windows of this building granite was not used, but a finer-grained stone procured from some distant part. The gable-cross on the transept, which was found in the chancel, and the corbel-heads hereinafter referred to, are of this stone. A coarse native sandstone was used in the construction of the Norman piscina in the chancel, and fragments of the same stone were used up elsewhere in later work.

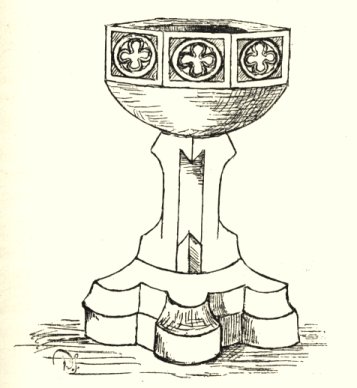

There is a good decorated font, which, before 1890, when it was restored to its pristine beauty, was covered with whitewash, and much mutilated. It had a piece of an iron drain-pipe fixed to it, while an earthenware basin was deposited inside the bowl. Indeed, the whole edifice previous to the restoration was in a very neglected state, with whitewash and green damp and rottenness everywhere. A rickety old kitchen table stood inside the altar-rails, and the floor of the chancel was paved with common red bricks.

Of the three bells, two are mediaeval and inscribed ‘Sancte Johannes, ora pro nobis,’ (Saint John, pray for us) ‘Sancta Maria, ora pro nobis’ (Saint Mary, pray for us).

ZENNOR FONT.

On the south wall of the tower is a small bronze dial, bearing the figure of a mermaid, and the inscription: ‘The Glory of the world Paseth. Paul Quick fecit, 1737.’

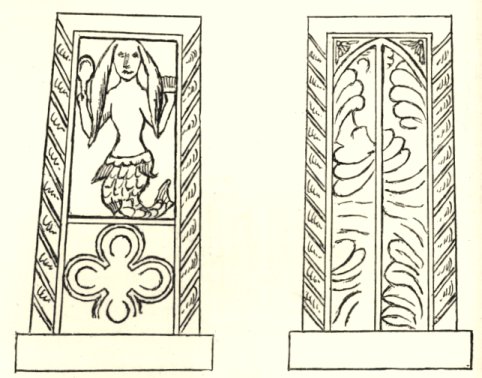

Until its restoration, Zennor church, the last in this district to be renovated, preserved for our instruction a sad picture of the surroundings amid which our great-grandfathers were content to worship. The original carved oak seats had all (with one exception) disappeared and been replaced by family boxes. Two old bench-ends only remained, on the south side, near the tower. One of them, known as ‘the mermaid of Zennor,’ is a great curiosity: it represents a syren with the conventional fish-tail, comb and mirror, which are held up in each hand; her long hair hangs over her shoulders and down to her waist. Such a subject is not out of place, in the church of a parish bounded by the sea; but folk-lore has constructed a marvellous story to account for it. The squire’s son, says the legend, sang so beautifully in the choir, that a mermaid came up from Zennor Cove to listen to his melodious voice. Falling passionately in love with him, she enticed him to return with her to the sea, and the ill-sorted pair were never seen again.

BENCH-END IN ZENNOR CHURCH, ‘KNOWN AS THE MERMAID OF ZENNOR.’

As, while this account is being written, the restoration of Zennor church is still proceeding, it will be well to note separately the ancient features which the careful work of the nineteenth-century architect (the Rev. Prebendary Hingeston-Randolph) has now brought to light. In the first place, as we have already mentioned, the windows have been refilled with good stone tracery, in place of the engine-house fittings which had disgraced them for about a century. The only old tracery which remained was in the perpendicular windows in the west wall of the tower and the west wall of the north aisle, and the decorated window in the south wall of the chancel. These have been simply repaired, and a good new three-light decorated window with hood-moulding inserted in the chancel, to the east of the last-mentioned old one, the design of which has been carefully imitated. A tall Early English lancet window (the existence of which was not suspected) has been reopened in the east wall of the chancel, a perpendicular one has been inserted in the east wall of the north aisle, and four very good windows of the same style in the north wall of the building. The supposed Norman light between the porch and the tower has been restored as a lancet of early thirteenth century work, which it proved to be. As we have seen, a large decorated window with geometrical tracery has been inserted in the south wall of the transept, a restoration in accordance with the slight traces of the original design which had been spared. One of the most important alterations in this building is the squint, by means of which the chancel can be seen from the transept. This squint opens at its south-western end with a flat-round double arch of ancient work, adapted, resting on a slender mullion; and the square passage runs obliquely through the thickness of the east wall of the transept, opening at its eastern end in the splay of the double-light decorated window in the south wall of the chancel.

WINDOW IN THE TOWER OF ZENNOR CHURCH.

There is a large piscina of early Norman work in the south wall of the chancel, and a small one of late date in the south-east corner of the north aisle.

Under the gable at the south-west angle of the south transept is a sculptured corbel head, which apparently represents a female face. Another corbel, which during the restoration lay loose inside the church, has been fixed in a corresponding position on the other side: it represents a man’s head, with long hair and beard.

A battered stone effigy of a saint was discovered behind some plaster in the niche on the west side of the tower wall. It is difficult to say whom the image represents. Between the legs of the figure is a skull.

The following are all the names of pre-Reformation vicars of Zennor which we have been able to collect:

| 1315. | Sir William de Arlyn. |

| 1320. | Sir Michael de Lamoren. |

| 1400. | John Wylla, chaplain, collated on the death ‘of John, the former Vicar.’ |

| 1416. | Nicholas Jory, chaplain, collated. |

| 1520. | Richard Smyth, ‘ clericus.’ |

According to the ‘Valor Ecclesiasticus,’ John Merrake was Vicar of Zennor in 1536.

The following is an extract from an essay on Zennor, written in 1889 by the Rev. Prebendary Hingeston-Randolph, the restorer of the church:

‘A word or two about the early history of Zennor church. It has long been served by Vicars, the Rectory having been appropriated on the Feast of St. Giles (1 Sept.) 1270, by Bishop Bronescombe, to the College which he had recently founded at Glasney, close to Penryn. His Register contains a copy of his Ordinance for the endowment of the Vicarage. It is dated on the Thursday next after the Feast of the Assumption (21 August), in the same year, and provides that the Perpetual Vicar should receive, yearly, the whole altalage; but the tithe of fish, wool, and beans, as well as of pease growing in the open fields, was reserved to the College. The house in which the Rectors had dwelt was to be, thenceforth, the Vicarage, and the Vicars were, also, to have the whole “Sanctuary,” or glebe. I cannot find that the name of any Rector remains on record, and the first Vicar who is mentioned is Sir William de Arlyn, who occurs on the 23rd of August, 1315, when Stapeldon was Bishop. The occasion was one of considerable importance to the said Vicar and to his successors. Bishop Stapeldon was on his Visitation at the time, and the Vicar of St. Senara appeared before him, and asked him to look to his endowment, which he complained was so small that it was impossible for him to pay his way. Stapeldon investigated the case, and took the poor Vicar’s part against the College. He talked the matter over with the Provost and Canons in their chapter-house at Glasney, and in the end succeeded in obtaining their unanimous assent to his proposals. The original endowment was cancelled; and better provision for Arlyn, and his successors for ever, was made, as follows: The Vicars were to continue to enjoy the Rectory house (or “manse,” as it is called in the Ordinance), with all the appurtenances thereof; also the whole altalage of the church, including, among other things, the tithe of hay throughout the parish, not only in all closes already existing, but in all that might be taken in at any future time; also the tithe of flax (linum) and hemp (canabum); of fish; and of all crops whatsoever growing in gardens existing at the time, or enclosed at any future time for spade-cultivation; and the tenth sheaf of Treveglos (a tenement which I do not find mentioned in the Directory) and of Bos (which I suppose is Boswednan). It seems that, for some time past, the College had been accustomed to help the Vicars a little, in their poverty, by an annual pension of twenty shillings, and this the Bishop told Arlyn he must not expect in future. The great tithes, together with the tithe of beans, peas, and vetches, growing not in garden-closes, but in the open fields, were reserved to the College. It transpired that the books and certain other things were in a dilapidated condition, and the Bishop ordered the College to pay twenty shillings to Arlyn for their repair, in two instalments—the first at Michaelmas, and the second at Easter in the following year at the latest. But in consideration of the large increase in the value of the Vicarage, he laid the burden of maintaining all these things, thenceforth, on the Vicar and his successors for ever. The ’Rectors (i.e., of course, the Provost and Canons) were to continue responsible for the fabric of the Chancel, except the roof thereof, which the Vicars were to maintain in good order, as well as the glazing of the chancel windows. Five years later Arlyn ceased to be Vicar. We are not told whether he died, or resigned the benefice; but on the 19th of December, 1315, he was succeeded by Sir Michael de Lamoren, who out-lived Stapeldon.’

The following are tombstone inscriptions at Zennor :

Agnes Champen, died 15 May 1731 aged 56. Erected by William her son. [The oldest in the yard; against the church-yard wall, south-east of the chancel.]

William Champen, born 14 October 1701, died 1790. Phillis his wife, born 8 March 1705, died 1791.

‘ Hope, fear, false joy and trouble

Are those 4 winds which daily toss this buble;

His breath’s a vapour, and his life’s a span,

Tis glorious mis’rey to be born a man.’

The next inscription is in the church. It is given in full in the second series of Bottrell’s ‘Traditions and Hearth-side Stories of West Cornwall’ as a literary curiosity. In his eulogium it is stated that the deceased ‘excel’d his equals.’ The tablet is fixed over an arch on the south side of the north aisle, near the chancel, and the body was interred in the same aisle, at the foot of the chancel steps. A granite slab in the floor at that spot bears the letters Iq and the figures 1784. The inscription commemorates

‘John Quick, of Wica, Yeoman:’ died 12th Septr 1784 aged 74 years. Also Wilmot his wife: died 20 July 1761 aged 41 years.

In Memory of Thomas Thomas, son of John and Mary Thomas of this Parish, and brother of Matthew; he departed this life on the 8th of March 1809 aged 26 years.

A rude granite headstone bears the terse inscription: ‘ J. T. A. 50, 1796.’

On the outside of the south wall of the church:

Sacred to the Memory of Matthew Thomas of this Parish, who was kill’d in Wheal-Chance Tin-Mine in Trewey Downs near this Church-Town, by a fall of Ground ye 16th of August 1809, aged 44 years.

’Belov’d by most, through all his well-spent life,

He left seven children and a loving wife,

Mourning their loss, their hearts wth grief oppress’d.

Weep not, but hope he’s mingled with ye blest.

By sudden death, his life’s short days are o’er,

A loving father and a friend no more.’

A. I. S. G.:

William Stevens of Trevalgen in the parish of St Ives ; Died 20 June 1831 aged 64.

Also Mary his daughter died l0th August aged 1 month.

Likewise Andrew his son, died 13 July 1815 aged 4 years.

Also Mary his daughter (another).

John Hollow, died 28 May 1844 aged 81 years.

Several members of the Borlase family in one vault.

William Drew, son of Thomas and Elizabeth Thomas and grandson of William and Elizabeth Drew: died 31 May 1861 aged 12 years.

Grace daughter of John and Catherine Thomas : died 7 April 1874, aged 20 years.

John Richards of Trevail in this parish, died 21 August 1877 aged 61 years.

The Zennor parish registers commence circa 1590, but the early portion has been almost entirely destroyed by damp. The first volume is a small quarto bound in calf. The first legible entry is

‘1618. Baptised Nicholas son of John Bereman.’

This book contains a list of the later vicars of Zennor, as follows:

John Whiteworth buried 1647.

John Morrack. Samuel Sweet buried 1655.

Richard Fowler buried 1669.

Anthony Randal buried 1683.

Benjamin Johns buried 1710.

John Oliver inducted 1711.

William Symonds inducted 1733.

William Borlase buried 1756.

Jacob Bullock inducted 1756 ; (removed to Wendron ; ‘his cession of Zennor entirely involuntary’).

William Borlase inducted 1768, (‘at the house of Samuel Bennetts, innkeeper in Penzance’); buried 1813.

William Borlase was also the name of the late vicar, who died in 1888. He was curate here so early as 1837. The present incumbent is the Rev. S. H. Farwell Roe.

On a flyleaf of one of the register-books is this:

‘ Elizabeth Stevens 1732

Of Zennor here

do writ when

this you see remember me

When I am out

of sight.’

Previous to the restoration (as we have said) most of the windows of Zennor church had had their ancient stone tracery replaced by paltry wooden sashes. On this point there is a story that a former vicar had the ancient windows put into his stable; but, in order that the church should not suffer any loss, he was careful to have the discarded stable windows put into the church. This would however seem to be only an idle tale.

Zennor church-town is disfigured by many deserted and ruinous houses, due to the emigration which of late years has deprived this and other once populous districts of some of its best blood. The contiguous parishes of Zennor, Towednack and Morvah are locally termed the ‘high countries,’ and preserve much of the social aspect of former ages. Here may still be commonly seen the immense open chimney, with dried furze and turf piled up on the earthen floor of the kitchen.

* I take it that the dedication of this church is to Saint Gwynog, or in English Winnock. According to Rees (‘Essay on the Welsh Saints’), Gwynog ab Gildas, a saint of royal British race, lived about the middle of the sixth century, and was a monk of Llancarfan. He is the titular saint of three churches in South Wales, and of Llanwynog, Montgomeryshire. In the chancel window of the latter church he is depicted, in glass of the fourteenth century, in abbatial robes, with a cross in his hand; below are the words ‘Sanctus Guinocus, ora pro nobis.’ Cressy says he founded the monastery of Saint Vinoc, on the confines of France and Flanders, and that his feast is in Brittany observed on the 6th November. In Wales his day is the 26th October. The parish of Landewednack, in the Lisherd District of Cornwall, and that of Landevenech in Bretagne, likewise bear the name of this saint. The syllable ‘To’ is a common prefix to the names of Cymric saints, and the ‘intrusive d’ before ‘n’ is familiar to students of Cornish.

Webmaster

Webmaster